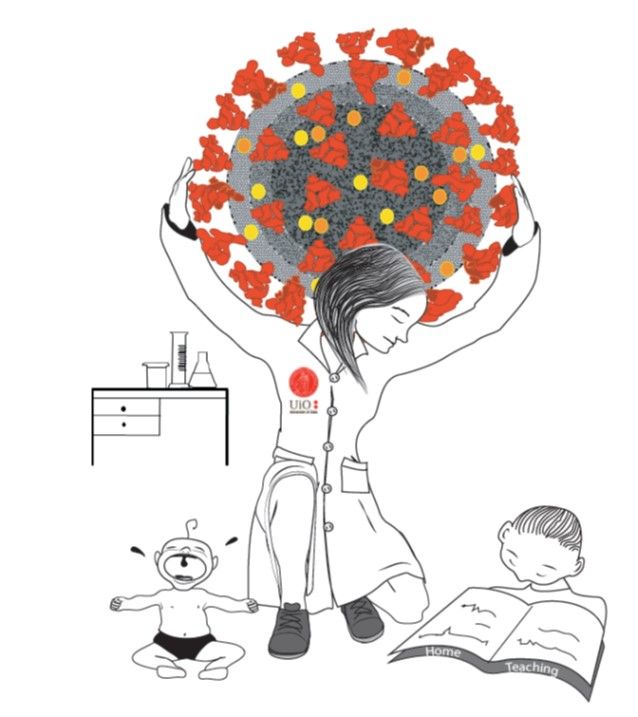

For some, this physical confinement could be ‘utilised’ to catch up on reading, writing and data analysis, since laboratory work was unfeasible while traveling and conferences were postponed or cancelled. For parents of young children though, this lockdown period became far more challenging. Members in the CanCell participated in a survey conducted by the CanCell Equality forum to map the impact of the COVID-19 restrictions. Although undoubtedly in most cases both carers of children were affected by the COVID-19 situation, the CanCell survey confirmed a worldwide trend that mothers of under-aged children were affected more severely (Figure 1).

A high number of CanCell members felt overwhelmed and faced difficulties in fulfilling their work duties during COVID-19 restrictions. The majority of those who answered that had been strongly affected were women and caretakers of children (Figure 2).

Here is a small insight into a day of four of these mothers during the COVID-19 lockdown.

We are going over the school work for the day. Our son wants to start with natural sciences: “How can you lift an ice cube with a piece of string?” He is in the first year of school and we are in COVID-19 lockdown. It is dad’s office day. He is sitting in the basement trying to focus on writing his research article. Our son has to work with English words, do math and read in a book for twenty minutes. And not to forget music homework. He has to finish making an instrument and play two songs with it. The choice was to make a guitar out of cardboard instead of the suggested maracas (a tin box and beans). The guitar has been glued together over night and needs strings. All homework and the school day should be meticulously documented with photos and text in the school app. After pouring salt on the ice cube and being able to lift it with the string, all documented on a video, our son is fed up and asks for a break. I am looking at the bread dough in the kitchen. Yeast has been impossible to buy and a friend brought me some yeast so I can finally bake bread again. Our three-year old daughter wants to do more puzzles with mum. I send our son to his room to play while I try to finish my email with a zoom code for a meeting after lunch. I find two puzzle pieces with Thomas the tank engine and two small hands puts them together.

٭ ٭ ٭

Life with a toddler is a fascinating experience, you learn by teaching them the mysteries of this world. But when a COVID-19 lockdown has put you in a small flat in the city centre with a raging toddler things get much more complicated. After a week of panic and depression for the lost hours of work, we decided that a home working space was necessary. We moved a desk in our bedroom, and that would be our home office. But how can you work, have meetings and concentrate when your toddler knows mum is around and cannot understand that she is not able to interact although she is at home? I had to wear my coat and scarf over my pyjama trousers and slippers. I kissed him goodbye and left “for work” running into our bedroom so he won’t see that I was lying to him. I had to stay in there for four or five hours and work in absolute silence. I learned that if I made the mistake to go to the bathroom, I would sacrifice my working day and I would have to make up for it until midnight.

٭ ٭ ٭

They are three and I am one. Daddy is locked in the office and I have replaced the usual routine of pipettes, hypothesis testing and manuscript writing with colourful plastic beads, sorting tasks in white baskets labelled with geometric symbols and trying to communicate with my oldest son by pressing on a synthetic voice generating app on his communication iPad. The easiest is to keep the exact same structure every day: weekdays, weekends and Easter. Up at 6.30, breakfast, one parent locked in the office for some hours of work, whereas the other plays special educator and day care assistant. After lunch we go out, one parent with the two younger to discover a half-drowned bug, a broken piece of plastic or a crooked stick a few meters from the house, the other parent with the oldest on his balance bike on the exact same daily two-hour long route. Then dinner, play time, kid’s bed time, a few hours of work for both parents – and repeat! The only deviation from the schedule is to somehow fit in the preparation of the school material. Four days ago, I printed all the material for the task in the white basket labelled with the yellow square. Three days ago, I cut out all the different objects from the printed pages into separate pieces. Two days ago, I laminated those pieces. Yesterday, I glued on the Velcro to facilitate the matching. Today, I assist in finding the yellow square on the list of tasks. The kids, my new reviewers, help with matching the yellow square from the list to the one on the basket and we bring the basket to the table. The task is new, and as expected, reviewer one is not pleased. Laminated sheets and cards with carefully aligned Velcro fly through the room and cover the living room floor. At least reviewer two and three pick up some of the cards with vegetable symbols on them and start playing grocery store. Still, it is a clear rejection. I can only hope that a careful rearrangement of the components of the task can lead to acceptance (with major revision) tomorrow. My moment of reflection is abruptly ended by the younger two reviewers starting a fight and dumping all the colourful plastic beads on each other. Daddy’s office time is over.

٭ ٭ ٭

As many mothers during COVID19 pandemic lockdown, I ended up trapped at home, forced to do home office and at the same time take care of my 16 months old daughter. A new day at home. Same every morning: I must find a new fun activity to occupy my daughter, knowing that she gets bored of playing with the same toys for more than two weeks now. I decided to take out "the creativity box" and my daughter loves it. Maybe this will excite her a bit since she likes to draw and paint? Also, I need to keep her busy for a little while, to finalize some work before the group meeting at 14.00 pm on zoom.

At 09.00 am I finally manage to sit down and my daughter is sitting next to me. She is very excited about the drawing session. I am supposed to work, but it is almost impossible when my little girl saying, “mamma” every ten seconds. She wants another colour pencil, to show me her drawing or is simply looking for some attention. I am replying with a smile on the face, or quickly grabbing her the red pencil that went on the floor. Despite everything I am still trying to keep focused. Suddenly it's 11.00 am, and it is time for some lunch before my daughters’ day-nap time. Finally, my daughter is sleeping, and can I enjoy this calm hour to be as productive as possible. I am hoping that my husband is back home from work on time to take my daughter to play outside while I attend my zoom meeting.

٭ ٭ ٭

Those women devoted much of their time to home-schooling and taking care of younger children. And while many were able to make equal time arrangements with their partners, some had full time day-to-day responsibility for their household and children. Those mothers struggled to keep up their work, and instead of making progress on their research papers or thesis, they were stuck with other chores, increasing the gap to child-free peers and male scientists.

Here it is important to point out that the difficulties female colleagues are facing amidst a pandemic, balancing childcare and career is not a “personal problem” but rather a systemic or structural constraint, the “motherhood penalty”, defining the gap in pay, opportunities and benefits between working mothers and child-free women and men. In addition, we need to take into consideration that many of our female colleagues are working under precarious contracts of two or three years (Crook, 2020). In a large-scale study conducted in Europe and the US and published in Nature human behaviour, researchers found that scientists have been disproportionally affected by COVID-19. From those, female scientists being mothers of at least one child of five years or younger have reported 17% decline in their research and productivity (Myers et al., 2020). We are already aware of the productivity gap, measured by publications rate in academia between male and female researchers. Far less women are sitting high in the academic ladder, and those women are less likely to have family obligations compared to their male colleagues (Hunter & Leahey, 2010)(Mccarthy et al., 2013).

We and others have shown that women in academia carry a greater burden of COVID-19 restrictions. Although Norway has been considerably less affected by COVID-19 than other countries around the world, the national academic institutions ought to act and identify solutions to prevent the deepening of the gender gap upon reaching the end of the pandemic. The University of Oslo has extended the working contracts for many PhD students and postdocs for workhours lost during the lockdown period. However, these measures are gender neutral and gender equality is therefore not addressed.

A decrease in research productivity of female students and scientists following the COVID-19 pandemic will influence their merit, career opportunities, promotions and academic choices compared to their male peers. Moreover, the increased stress during the pandemic has also influenced work productivity and amplifies pre-existing inequality. Our female scientist mothers will not have been as successful in submitting and winning research grant applications during the COVID-19 period.

Recognising the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on gender bias is necessary to find appropriate solutions in academia upon our return to a relative normality. The academic institutions have to study and address the impact of COVID-19 measures on gender and other marginalized groups. Raising awareness and implementing policies that will help facilitate a reduction the gender gap in academia is a critical and necessary step. We believe in the necessity that reviewers of academic recruitment committees and funding bodies are made aware of the impact of this pandemic on gender imbalance in order to be able to conduct fair evaluations. Female PhD students and scientists must be given support and time to be able to complete their research publications, thesis or grant applications, potentially by being exempted from service or teaching duties for some time. Institutions have to act now to ensure a strong interdisciplinary, innovative and diverse academic environment.

You can read more about this topic here:

Crook, S. (2020). Parenting during the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020: academia, labour and care work. Women’s History Review, 0(0), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/09612025.2020.1807690

Hunter, L. A., & Leahey, E. (2010). productivity : New evidence and methods. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312709358472

Mccarthy, C., Ann, M., Wolfinger, N. H., & Goulden, M. (2013). Do Babies Matter ?: Gender and Family in the Ivory Tower Doctored : The Medicine of Photography in Nineteenth-Century America. 160–161.

Myers, K. R., Tham, W. Y., Yin, Y., Cohodes, N., Thursby, J. G., Thursby, M. C., Schiffer, P., Walsh, J. T., Lakhani, K. R., & Wang, D. (2020). Unequal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on. Nature Human Behaviour. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0921-y

You can also check:

Mothers in Science (www.mothersinscience.com)

Parents in Science (www.parentsinscience.com)

Mama is an Academic (www.mamaisanacademic.wordpress.com)

.jpg?alt=listing)