Please visit the event page here

This report has been published by Conflict and Health

CHALLENGES

“Peace is essential and in fact, non-negotiable to ensure a healthy, productive global population” (1). SDG16 - promoting, peace justice and strong institutions is thus indivisible from the health goal SDG3 - promoting good health and wellbeing.

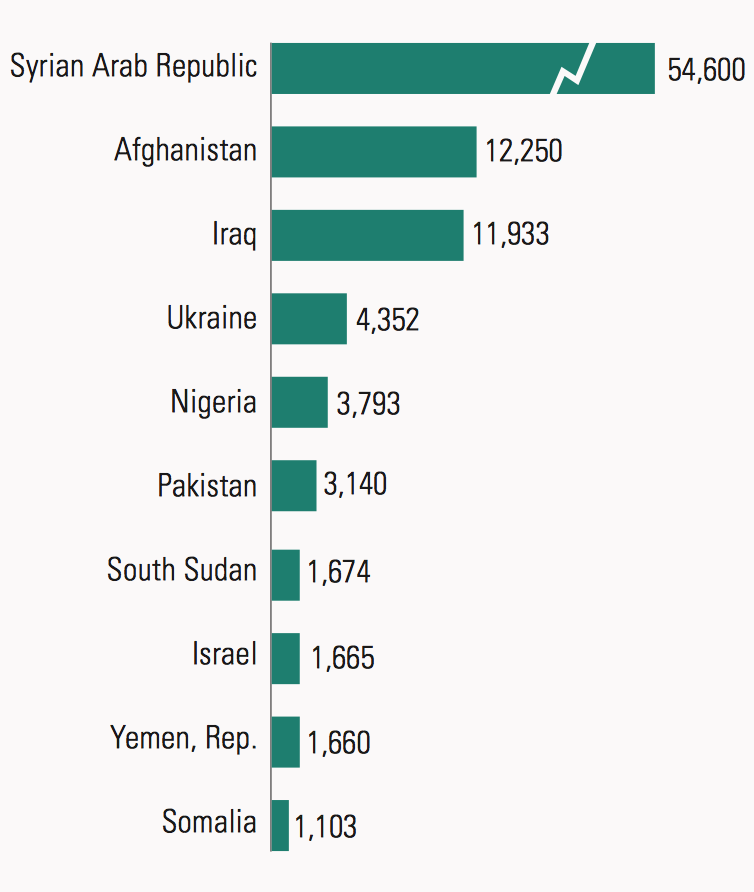

In their 2016 Human Development Report - Human Development for Everyone (2) - the UNDP review conflict-related statistics, showing that for several decades after the end of the Second World War, there has been a downward trend in war-related deaths (except in 2000, with the war in Eritrea–Ethiopia killing 50,000+ people). With the escalation of conflict and extreme violence in the Syrian Arab Republic, 2014 saw the highest number of battle-related deaths since 1989 (Figure 1).

Maintaining and providing health care services in these settings pose unique and extremely difficult challenges, which vary depending on the context, the type of conflict and the actors involved, the local systems and populations and the humanitarian space available to provide aid. Many of these challenges and some potential solutions were highlighted at the conference by medical doctors, humanitarian workers, scholars and politicians.

Increase in global conflict, death and displacement

“On a global scale, we are using 1000 times more on military hardware than we are using on humanitarian issues and development” - Robert Mood, President of the Norwegian Red Cross

.png)

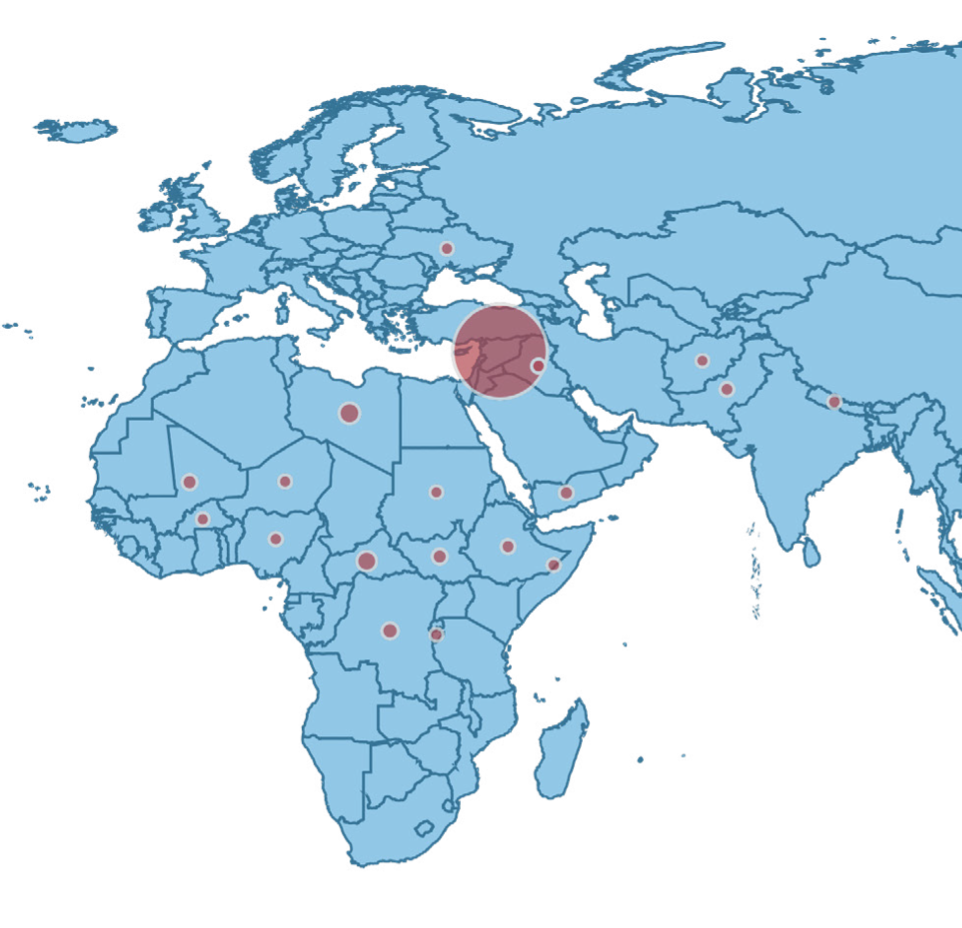

Incidents of violent extremism and terrorism worldwide tripled between 2006 and 2014 and between 2000 and 2014, there had been nearly a tenfold increase in deaths. And yet the $742 billion a year lost due to conflict dwarfs the $167 billion in annual official development assistance. On top of the losses of life and economic losses, people are uprooted, losing their lifestyles as well as their belongings and their families are broken up (Figure 2).

Health care in crisis: Destruction, decay, denial and danger

Health systems in many conflict situations face several layers of challenges. Hanna Kaade, a medical doctor from Syria, described the decay and deterioration of the health system during the war in Syria. “Out of 1,787 public health centres, each of which serviced more than 5000 people, 540 were completely out of service,” Hanna said. The majority of the health centres were destroyed and many were taken over by armed groups. The larger public hospitals endured a similar fate. It is no surprise, therefore, that doctors were the first to leave the country due to being threatened, kidnapped and killed.

This destruction and decay of the health care system and services have profound effects on the local population and not just the injured, but also those suffering from chronic and other medical conditions. There is a diminished capacity to address infectious disease outbreaks, like the current epidemic in Yemen, which will reach around one million cases by the end of the year. Furthermore, decay of the health care system has prolonged effects that last well beyond the conflict itself. As Frederik Siem from the Norwegian Red Cross described, during a typical five-year conflict, infant mortality rates increase by 13 % and remain at a 11 % higher rate than at baseline for the first five years post-conflict (3,4). Meanwhile, women are more likely to schedule caesareans and give home births, because it is dangerous to spend too much time in hospital.

Additionally, the cut off from supply chains, electricity and water, often used strategically in warfare to weaken the population, radically decreases the capacity of the health care system to continue to function (3). Demonstrating this, a review of nine armed conflicts in sub-Saharan Africa concluded that deaths in battle accounted for 6−8 % of deaths, the vast majority being caused by disease and malnutrition (5).

Attacks on health care personnel

With the changing climate of warfare and conflict, attitudes towards medical personnel have also shifted and not in the positive direction. Morten Rostrup gave an account of the years he had spent working with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) International, in which he saw a shift towards denial of health care and attacking health personnel as a weapon of war. Working in a refugee camp in the Democratic Republic of Congo at the time when the Kabila forces attacked hundreds of thousands of Rwandan refugees - “if you work in the conflict zone,” said Morten, ”the safest place you can be in is the hospital, because it is a respected place.” The International Humanitarian Law (IHL) ensured protection of all medical personnel and services. He felt equally safe during the bloody civil war in Angola.

Morten recalled a shift in dynamics around 2001, while he was in Afghanistan. He entered Kandahar in December, after the 9/11 attacks and right after the American and Afghan military had forced the Taliban out of Kandahar. In Kandahar city, there were civilian military personnel, that is American soldiers in civilian clothing with hidden guns driving civilian cars. At the same time as the Americans were bombing Afghanistan with the aim of dismantling al-Qaeda, they were also distributing packages of food from the planes to people. This confusion was exemplified in an experience, where during an explo mission[1] in the Helmand province, while completely visible and marked with the MSF vest, Morten was asked whether he was an American soldier.

This confusion between the military and health care/aid personnel was sounded out just months prior to this, on the 26th of October 2001, by Colin Powel, the then foreign minister of the US, who spoke with American non-governmental organisations (NGOs): “As I speak, just as surely as our diplomats and military, American NGOs are out there serving and sacrificing on the front lines of freedom. … I want you to know that I have made it clear to my staff here and to all of our ambassadors around the world that I am serious about making sure we have the best relationship with the NGOs who are such a force multiplier for us, such an important part of our combat team” (6). The danger that this message carries is that aligning NGOs with the military, the military potentially aligns them with legitimate targets in a war.

In March 2011, during the civil war in Libya, Morten was a witness to an attack, while speaking on the phone to Libyan doctors working in Zawiya - people carrying injured patients were killed, blood banks were destroyed. “It was very deliberate,” said Morten, “to deny health care was used as a weapon of war.” The hospital continued to be under attack and had to be evacuated. In 2012, in Qamishli, the north of Syria, Morten recalled being told for the first time to conceal the fact that he was a doctor. The changing climate meant that it was more dangerous to be caught with a patient that is suspected to be part of the opposition than be caught with a weapon.

Irregular violence - health care strategically targeted

Summarizing these events of escalating violence and the intention of violence towards health care and aid workers, Scott Gates and Håvard Nygård, from PRIO, presented data on the deaths of these professionals during conflict (7). These data show that over 1500 medical workers have been attacked just since 2014. Many more have been threatened, injured, or kidnapped and tortured. This targeting the non-belligerents, but also the systematic deprivation of people’s access to food, health and education, expanding the scope by which conflict occurs has been termed “irregular violence.”

Unsurprisingly, the data show a strong correlation between irregular violence and the explosion of battle casualties that occurred during and after 2014, especially in Iraq and Syria (Figure 3) - the more intense the conflict, the more likely that health workers are attacked. Something peculiar, however, is that there is no observed correlation between attacks on civilians and aid/medical workers. The implication is that health workers are targeted, rather than caught in the crossfire.

The expansion of ‘humanitarian actors’ – who are they anyway?

To add to some of the challenges blurring the lines between humanitarian actors and the military, there is increasing confusion between humanitarian actors themselves. The humanitarian label carries with itself peace and neutrality and is, therefore, popular. However, not all self-labelled humanitarian actors maintain the functions of neutrality, which can lead to mistrust and confusion on the ground. In addition, humanitarianism is politicized and looked upon as a western intervention, or is sometimes brought in for peacekeeping, promoting democracy and becoming involved in military operations, such as the case with the UN. In fact, a general shift has been observed, where some humanitarian agents are becoming increasingly active in human rights advocacy, thereby putting doubt over their claims of impartiality (8).

Women in conflict

“…Conflict does not affect women and men in the same way or in the same proportions. Realities that are experienced differently by women and men are hidden behind the statistics on human and economic losses.”[2] (9).

“Not only does violence against women increase and accelerate in war situations,” stated Johanne Sundby, a Professor at the University of Oslo, “but also it is strategically used as a war tactic against the civilian population. It is therefore particularly important as part of a health care system in crisis to address violence, sexual abuse and issues of rape, reproductive care and abortion.”

Specialised maternal, newborn and antenatal care packages, the Minimum Initial Service Packages (MISP), do exist in these settings, however many of the services are developed based on experience alone, while evidence is still lacking for what is most effective in these situations. Additionally, Johanne talked about the importance of post-conflict restructuring and rebuilding of health systems to address the issues that arise during conflict, especially targeted at vulnerable populations such as women and children.

SOLUTIONS

International Humanitarian Law and a challenge for neutrality

“What we see is impunity. We do have laws and war crimes and it doesn’t have any consequences on what people do and now we have state actors committing these war crimes. What we should do to increase respect for IHL is put up mechanisms in which people are accountable.” – Morten Rostrup

Medical neutrality refers to a globally accepted principle derived from International Humanitarian Law (IHL), International Human Rights Law and Medical Ethics. It is based on principles of non-interference with medical services in times of armed conflict and civil unrest. It promotes the freedom for physicians and aid personnel to care for the sick and wounded, and to receive care regardless of political affiliations. Concomitantly, attacks on and misuse of medical facilities, transport and personnel for political means are condemned.

The recent escalation of attacks on medical and aid personnel emphasizes the need to strengthen the legal instruments and consequences of war crimes, and challenge those who do not follow them. An example of this can be seen in the current Counter-Terrorism Law in Syria, which declares that medical facilities operating in opposition-held areas are legitimate targets of military violence (10). There are, however, positive examples such as Serbia that sanctioned the unauthorized use of Red Cross emblem with fines. Or Mexico, where it is now illegal to compel medical personnel to witness or testify based on patient information, and it is also illegal for judges and prosecutors to make such evidence admissible in court (10).

To protect the integrity of international legislation, it is also necessary to independently assess and be critical of potential war crimes on all sides and to make a case that the IHL is universal and applies to everyone.

Non-instrumentalisation of humanitarian and medical workers

The answers to why these changes are occurring and why the rules are being broken are complex, multifaceted and context dependent. Several possible explanations were brought up in the course of panel discussions. One is that IHL is becoming more politicized and is being exploited or instrumentalized for peace negotiations. As a consequence, the legitimacy of the law is challenged, weakening its neutrality and power. Catherine Andersen from the Section for Humanitarian Affairs, Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, suggested being open to discuss this issue for each and every situation. “It is extremely difficult to make sure that humanitarian aid is not instrumentalized, but having a dialog is not politicization of aid.” To do no harm is the key principle that organisations and their funders are accountable for.

Another solution is to question the actions of humanitarian organisations and their protocols. The actors in the field need to be brave enough to criticize humanitarian organisations that are themselves violating the rules, carrying weapons or becoming closely tied with military forces.

National Governments and the responsibility to protect

“We want vigilance to ensure compliance by the states to the principles themselves such as international humanitarian law. But also taking practical steps to ensure the safety of health care personnel and facilities from attack.” – Robert Mood

The Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs became more systematically engaged on the issue of attacks on humanitarian aid workers after the 31st Conference of the International Committee of the Red Cross and Red Crescent in 2011 where the Health Care in Danger initiative was launched (11). “As governments, we are not humanitarian actor, we are states with humanitarian obligations to protect and allow humanitarian systems to take place within conflict”, commented Catherine Andersen.

Local needs, local populations, local solutions, local data

“Two key elements of success are visible - access and knowledge. We must capitalize on our local knowledge and science from communities to develop and refine effective and practical responses.” – Robert Mood

Humanitarian response requires appropriate, contextual and quality conflict event data, including:

- Battle deaths – What happened? How many people were killed? How many casualties are there? Are they civilians or combatants?

- Geographical and temporal data - The time, length, location and actors involved in an event.

- Onset data - What happens before and after an attack?

- Health and medical status - What happens to the population, health indicators like maternal and child health, disease outbreaks?

- Implementation data - Most importantly, there needs to be knowledge and information about how to both implement effective strategies and how to get access to vulnerable populations.

Humanitarian space needs to exist in order to assess the situation, provide relevant information to aid and medical personnel, and provide the aid. Hanna Kaade described some local knowledge that his colleagues used in order to create such humanitarian space while working in Syria. “We used the three Cs - coordination, cooperation and communication,” said Hanna, “it is important to develop relation and communication with the kind of groups you did not think the hospital or ambulance services should be in contact with - armed groups – in order to gain access and pass checkpoints.”

There is an increasing need to focus on the local communities long term to prevent health care from being destroyed and all the doctors and teachers leaving. “Everything that makes a country a country, everything that makes a community a community, that gives people an opportunity to survive in a place, to have a life – it is run by locals.” Catherine Andersen

Protecting and rebuilding health care systems

The way in which people are protected during the conflict determines what happens afterwards. What happens during the war must be done with the consideration of how people will return. Will the refugees want to return? How can reconstruction happen and trust rebuild if all the rules were broken during the war? Therefore, health care is a vital service of the society but is also part of something greater – protection and development.

Hanna Kaade agreed, from his personal experience in Syria and from the side of the affected people, to see reconstruction on the ground breeds optimism and makes people stay in their home country.

CONCLUSION

“As we enter, united, into these next 15 years, we would be well served to remain aware of the crucial role that SDG 16 (peace, justice, and strong institutions) has in the achievement of SDG 3. Politics and health are inextricably linked, and we cannot expect to eliminate health inequities for the most vulnerable populations if we sit back and let the injustices of war reign supreme.” (1)

The denial of health care and the use of health care as a weapon is a challenge to take on immediately and with a lot of effort and energy. The drivers of violence are complex and thus call for a multipronged approach that includes promoting the rule of law based on fairness and zero tolerance for violence, strengthening the local response, supporting the local health providers and developing support services to address violence and its victims. This is difficult and requires cooperation between states, the academic and humanitarian sectors. Resilience needs to be supported and maintaining, protecting and rebuilding the health care system must be high priority during and after conflict.

The close link between health and peace creates a barrier to reaching SDG3 unless new approaches are designed to more effectively engage in conflict areas. In order to develop the most effective ways to engage and understand what approaches work best in which scenarios, better data and information is necessary. Therefore, this is a call for the research/academic sectors in conflict/peace research and in global health research, to work together towards achieving SDGs 3 and 16.

References

1. Wesley H, Tittle V, Seita A. No health without peace: why SDG 16 is essential for health. The Lancet. 2016 Nov 12;388(10058):2352–3.

2. Human Development Report Office. 2016 Human Development Report: Human Development for Everyone. 2016 [cited 2018 Jan 9]. Available from: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2016_human_development_report.pdf

3. Siem FF. Leaving them behind: healthcare services in situations of armed conflict. Tidsskr Den Nor Legeforening. 2017 [cited 2018 Jan 9]. Available from: http://tidsskriftet.no/en/2017/09/kronikk/leaving-them-behind-healthcare-services-situations-armed-conflict

4. World Bank. Breaking the conflict trap. The World Bank. 2003. 220 p. [cited 2018 Jan 9]. Available from: https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/978-0-8213-5481-0

5. Human Security Centre. Human Security Report 2005: war and peace in the 21st century. Oxford University Press. 2005. 178 p.

6. Secretary Colin L. Powell. September 11, 2001 : Attack on America remarks to the national foreign policy conference for leaders of non-governmental organizations. 2001 [cited 2018 Sep 1]. Available from: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/sept11/powell_brief31.asp

7. Gates S, Mokleiv Nygård H, Bahgat K. Patterns of attacks on medical personnel and facilities: SDG 3 meets SDG 16. Confl Trends. 2017 [cited 2018 Jan 9]. Available from: https://www.prio.org/Publications/Publication/?x=10785

8. Leebaw B. The politics of impartial activism: humanitarianism and human rights. Perspect Polit. 2007 Jun;5(2):223–39.

9. UN Security Council. Security Council resolution 1325 (2000) [on women and peace and security]. 2000 [cited 2018 Jan 9]. Available from: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3b00f4672e.html

10. Gregory D. The death of the clinic. Geographical imaginations: war, space and security. 2016 [cited 2018 May 1]. Available from: https://geographicalimaginations.com/tag/medical-neutrality/

11. International Committee of the Red Cross and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Report of the 31st International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent – Including the Summary Report of the 2011 Council of Delegates. Geneva; 2011 [cited 2018 Jan 10]. Available from: https://www.icrc.org/en/publication/1129-report-31st-international-conference-red-cross-and-red-crescent-including-summary

[1] An “explo” or exploratory team of experienced MSF staff is dispatched in situations of a potential emergency – such as an outbreak, a natural disaster, or people fleeing violence to assess the response required to the real medical needs on the ground. http://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/under-radar

[2] Paragraph 3 of the UN Security Council resolution 1325.