Data from the 2015 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study found that when adjusted for age, depressive disorders were the fourth leading cause of disability in 2005 and the third leading cause of disability in 2015 (1). The 2015 GBD study reported a positive association between conflict and depression and anxiety. While almost everyone who had lived through conflict situations suffer some form of psychological distress, accumulated evidence shows that 15-20% of crisis-affected populations develop mild-to moderate mental disorders and 3-4% develop severe mental disorders such as psychosis or debilitating depression and anxiety (2). If detected too late or left untreated, mental disorders can increase in severity, result in worse treatment outcomes later and have a huge impact on both individuals and societies (3).

Several issues have been highlighted during the seminar, including the lack of global funding allocated to mental health, despite the fact that one of the top GBD outcomes has been attributed to it; a slow and often complete lack of response to the mental health diagnosis of vulnerable populations; endangering people’s lives by creating conditions for refugees from conflict affected countries that would exacerbate stress and mental instability; and the lack of important research and data that would support scaling up successful mental health interventions.

Mental health and data

Despite the known GBD from mental disorders, there are still many barriers for addressing the issues. The first is the negligible amount of money allocated to mental health from global pool of funds, the second is the quality of data available for mental health intervention and the last is research on the scaling up of successful interventions. Bayard Roberts from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine discussed some of these factors and addressed the social determinants of mental health disorders in displaced and conflict-affected populations.

Although not all conflict-affected persons are affected by mental disorders, and many who are affected self-recover, a large percentage will require some form of intervention, including a small percentage (2-3%) that have severe or pre-existing mental health needs.

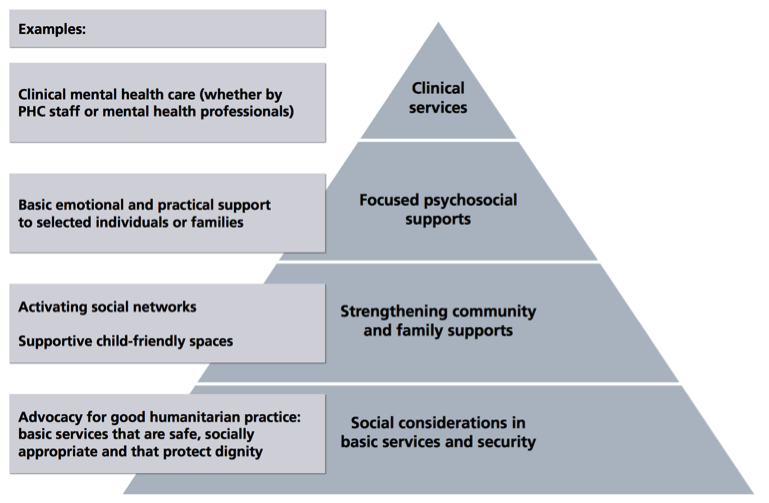

A lot of research and knowledge revolves around the bio-psychiatric (or western) approach such as specialist support and the psychosocial approach. Increasing evidence shows, however, that involving the community and addressing the essential basic needs is most commonly applied (Figure 1). Therefore, there needs to be more research in community-type settings, highlighted Bayard.

Furthermore, there are little deliberate efforts to increase the impact of health service innovations of successfully tested interventions to benefit more people and to foster policy and programme development on a lasting basis. Despite the need to expand coverage of services, without evidence and a systematic approach, mental health and psychosocial support service pilot projects are rarely scaled up (5).

The four key elements for scaling up include:

- Evidence of effectiveness:

Most of the interventions are at the community and psychosocial levels, but most evidence is coming from experts. - Evidence on cost/cost effectiveness:

Mental health publication numbers are high, relative to other health topics, and the quality of the research is better than some other sectors, however very few studies included cost data. - Understanding of the process of implementation:

Randomised control trials would help understand the process pathway of success from intervention to outcome. Key pathways of implementing interventions need to be understood so that they can be expanded. - Understanding of the health system in which services will be scaled up:

Using elements of the WHO health systems responsiveness domains (6), assess the health system based on:- autonomy

- choice

- communication

- confidentiality

- dignity

- quality basic amenities

- access to care

- prompt attention

- support

Forced migration, mental health and vulnerability

The ongoing conflict and displaced local and refugee populations in Africa, the Middle East and the rest of the world compound mental health needs of affected populations, but the mental health aspect of these crises is often overlooked. Nora Sveaas from the Department of Psychology at UiO gave a human rights perspective on the identification and treatment of vulnerable asylum seekers. Nora had been involved in research and advocacy for vulnerable asylum seekers, especially victims of torture and has visited detention centres in many places in the world. Her main message was that rights and obligations are now being questioned, by states who themselves have adopted them - “Human rights are under siege.“

Based on what we know about the risk of mental health disorders in refugees and asylum seekers, there is a much lacking need for early assessment to detect mental health disorders. “Even during short stays identifying disorders and offering services can be lifesaving”, said Nora. But instead, many refugees, including children and women are enduring sexual and physical violence, abuse and denial of rights by countries who do not fulfil their obligations.

Chapter IV, Article 21 of the Directive 2013/33/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council states:

“Member States shall take into account the specific situation of vulnerable persons such as minors, unaccompanied minors, disabled people, elderly people, pregnant women...” (7). And yet many European Member States are themselves complicit in abuse in order to discourage refugees from crossing their borders. European states are not the only violators of such human rights. The ill treatment of asylum seekers on Nauru Island by the Australian government continues to be disputed by both the local and global communities. “We must remind states of their obligations”, Nora emphasised.

Besides her advocacy and research, in order to create evidence-supported change, Nora had been involved in setting up an Internet database of resources for health and other professionals working with vulnerable people - HHRL.org. The database includes studies that have been conducted to develop ways in which to identify vulnerable asylum seekers and need to be implemented as part of legal processing.

The impact of war and conflict on children

Matthew Hodes from the Imperial College London described the demographics of children and young refugees in settlement countries and risk factors for psychological disorders within this population. The number of asylum applicants considered to be “unaccompanied minors” in the EU Member states between 2008 and 2016 currently exceeds 100,000 (Figure 2), many of them coming from the Middle East. Depressive symptoms arise due to hopelessness and negative experiences in the new country, such as lack of money, racism and discrimination. The threats to mental health in children are ongoing. Due to the risk of refusal of asylum in a host country and subsequent deportation as a child approaches the age of 18 they became more stressed. These high levels of stress can trigger psychosis and increased suicidal behaviour.

Accompanied children experience another kind of trauma in relation to their parents. Not only are the children, themselves, coping with massive losses, and changes in family life and routines, but also parental mental health has an effect on child mental health as well. Studies show that maternal PTSD is associated with mental disorders in children due to attachment insecurity. Attachment security is necessary to create a secure environment from which a child can develop and explore. However, with mental disorders and unpredictable behaviour in parents, the child does not have the opportunity to rely on them for security. The outcomes are children with lower self-esteem, high aggressive behaviours and increased conduct disorders, including conflict with older children.

Espen Gran, Save the Children Norway, presented results from a study conducted with recently displaced children who had been living relatively short term (<3 years) and for a prolonged time (>3 years) in ISIS occupied areas (9). For this report, Save the Children staff and partners spoke to 458 children, adolescents and adults inside seven of Syria’s 14 governorates.

The results showed that those, who had lived for a shorter time in occupied territories, were more likely to be protected by their parents and have fewer symptoms of mental illness. Conversely, those who lived for a prolonged time in occupied areas and, therefore, were more likely to have witnessed death and violence, lived with a constant fear of violence and punishment and showed signs of severe emotional distress. They appeared desensitized and were not able to show any expression of joy. Even for those who had family members accompanying them, the families themselves were tired and exhausted, and therefore were not able to fulfil their role as parents to give the type of care that the children would need. Other results that come out of the study include:

- Bombing and shelling is the number one cause of psychological stress;

- Two out of three children have lost a loved one or had their house bombed or shelled or suffered war-related injuries;

- 80% said children and adolescents have become more aggressive;

- 71% said children increasingly suffer from frequent bedwetting and involuntary urination, both common symptoms of PTSD in children;

- 49% said children regularly or always have feelings of grief or extreme sadness and 78% of children have feelings of at least one at any time. (9)

Women in conflict - Ukraine

Starting from 2013, Ukraine has been experiencing various shocks such as mass protests, annexation of Crimea, armed conflict, violence, which led to the death of many and even more displaced. The majority of internally displaced people (IDP) are women, children and the elderly. Both the civilian population and the servicemen and women involved in conflict are under extreme pressure. And there is a large treatment gap for mental health disorders with 74% of people not receiving the required treatment (10).

Iryna Pinchuk, the Director of the Ukrainian Scientific Research Institute of Social and Forensic Psychiatry and Drug Abuse, Ministry of Health of Ukraine, presented some data relating to the mental health situation in Ukraine. “Women do everything”, stated Iryna, “they look after children, family members, the house, and still the number of women participating in fighting is constantly increasing.” Currently, over 55,000 women are in regular military service, including 3100 officers.

There is an observed difference between the mental health conditions of men and women. Specifically, the prevalence of mental disorders among men exceeds that of women, and men are more likely to seek help from psychiatrists, whereas women go to family doctors. Women suffer more commonly from affective and neurotic disorders as well as dementia, whereas men are more likely to suffer from depressive disorders and anxiety as well as PTSD, and have problems with alcohol abuse.

“In conflict conditions, sexual and physical abuse of women and children increased “, Iryna reported. Twenty-two per cent of women between the ages of 15-49 had at least one experience of physical or sexual violence, although only around 30% of cases are actually reported. There has been an increase in sexually transmitted infections including HIV, as well as pregnancy among adolescents. Military personnel are some of the perpetrators of the abuse. Women say that they are forced into sexual contact with military personnel to ensure safety for their family.

However, the conflict in Ukraine also brought these issues to light. While the global community is watching, it is a good time to put pressure on local politicians to act - “Now is the time to review the national mental health policy with special attention to needs of women,” concluded Iryna.

The coping strategies of peacekeepers

Peacekeeping is a military operation undertaken by the UN and other international actors to maintain peace in hostile areas. Preventing disputes and escalating tensions, and trying to bring the opposing parties to the negotiating table when the hostilities are in progress are the two main tasks of such operations (11). Lars Weisæth from the Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies and the Institute of Clinical Medicine at UiO, has been to 55 peacekeeping operations and offered his experience on the difficulties of being a military observer and a peacekeeper with the UN.

Observers are unarmed. Part of their job is to maintain neutrality and investigate attacks. “Successful coping”, said Lars, “is a realistic understanding and acceptance of the observer role with its duties, limitations and risks.” The difficulties of the job can have gruelling effects on the peacekeepers. They must observe the rules of engagement even when their patience and honour is challenged; they must protect the legitimacy and credibility of their mission and the organization that they work with by restraining themselves during deliberate provocation, even if it is an attempt on their life; and they must make on-the-spot decisions in situations where they have little information of a potential threat. The inability to respond to atrocities and violence due to the strict rules of engagement is described as the peacekeepers acute stress syndrome (9) and can lead to psychological distress and PTSD.

Lars described his experience with peacekeeping in South Lebanon where psychological conditions were the most common reasons for termination and repatriation on medical grounds. Normal protective mechanisms in combat situations include team coherence and trust in leadership, military competence and training. Although these have been improving with time, Lars reflected that they had not been sufficient in the past and much repatriation had happened due to psychological injuries. The internal conflict of a peacekeeper is between strong aggressive impulses seeking an outlet and inability to express them (except for self-defence) as well as the difficulties of coming back to civilian life.

Conclusion

Mental health disorders contribute a large part to global disability. The positive association between conflict and poor mental health, especially in children and other vulnerable populations is clear. This evidence forms support for global action to make mental health a global development priority and improve the availability of both services and research for conflict-affected populations. As varied mental health difficulties are experienced across the lifespan, early detection and a tiered system of care are necessary to address mental health challenges in refugees and asylum seekers. The tiered intervention system includes: universal services consisting of primary care (Tier 1); combination of specialist and community-based interventions (Tier 2); specialist multidisciplinary outpatient care (Tier 3); and highly specialised inpatient care (Tier 4).

“We need to move beyond immediate and acute and think about longer term results. We need to be more ambitious about the type of care that we should be providing” – Bayard Roberts

References

1. Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet. 2016 Oct 8;388(10053):1545–602.

2. Marquez PV. Mental health services in situations of conflict, fragility and violence: What to do? Investing in Health. 2016 [cited 2018 Jan 9]. Available from: http://blogs.worldbank.org/health/mental-health-services-situations-conflict-fragility-and-violence-what-do

3. Kleinman A, Estrin GL, Usmani S, Chisholm D, Marquez PV, Evans TG, et al. Time for mental health to come out of the shadows. The Lancet. 2016 Jun 4;387(10035):2274–5.

4. WHO and UNHCR. mhGAP Humanitarian Intervention Guide (mhGAP-HIG). WHO 2018 [cited 2018 Jan 9]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/mhgap_hig/en/

5. Eaton J, McCay L, Semrau M, Chatterjee S, Baingana F, Araya R, et al. Scale up of services for mental health in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Lond Engl. 2011 Oct 29;378(9802):1592–603.

6. Gostin LO, Hodge JG, Valentine N, Nygren-Krug H. The domains of health responsiveness : a human rights analysis. WHO Institutional Repository for Information Sharing. 2003 [cited 2018 Jan 9]. Available from: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/73926

7. European Union: Council of the European Union. Directive 2013/33/EU of the European Parliament and Council of 26 June 2013 laying down standards for the reception of applicants for international protection (recast), OJ L. 180/96 -105/32; 29.6.2013, 2013/33/EU. 2013 [cited 2018 Jan 9]. Available from: http://www.refworld.org/docid/51d29db54.html

8. Eurostat. Press release : 63 300 unaccompanied minors among asylum seekers registered in the EU in 2016 – Over half are Afghans or Syrians. 2017 [cited 2018 Jan 9]. Available from: https://article.wn.com/view/2017/05/11/63_300_unaccompanied_minors_among_asylum_seekers_registered_/

9. Save the Children. Invisible wounds: The impact of six years of war on the mental health of Syria’s children. 2017 [cited 2018 Jan 9]. Available from: http://www.savethechildren.org/site/apps/nlnet/content2.aspx?c=8rKLIXMGIpI4E&b=9506655&ct=14987359¬oc=1

10. Roberts B, Makhashvili N, Javakhishvili J, Karachevskyy A, Kharchenko N, Shpiker M, et al. Mental health care utilisation among internally displaced persons in Ukraine: results from a nation-wide survey. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2017 Jul 27;1–12.

11. Raju MSVK. Psychological aspects of peacekeeping operations. Ind Psychiatry J. 2014 Jul-Dec;23(2):149–56.