Basic facts about Zika

The Zika virus is mainly transmitted through the bite of an infected Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquito (the same mosquitoes that spread other tropical viruses such as dengue and chikungunya). It can also be transmitted sexually and through blood donation, but other modes of transmission may yet to be discovered.

Zika can be asymptomatic or have symptoms similar to other mosquito-borne infections like dengue and chikungunya, which include fever, rash, joint pain, conjunctivitis, headaches and muscle pain. The symptoms are usually mild and many people might not realize they are infected with the virus and consequently not be tested.

A pregnant woman can pass Zika virus to her fetus causing the fetus to develop with microcephaly (reduced head size and incomplete brain development) and other severe fetal brain defects. The mechanism of infection leading to microcephaly and birth defects is yet unknown. The full range of potential health problems is currently being studied by the Centre for Disease Control (CDC).

Long lasting symptoms in adults are uncommon, however the Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) – an autoimmune syndrome that attacks the peripheral nervous system – has been associated with the Zika virus infection. The symptoms may include weakness in the limbs and difficulty breathing. Most people fully recover from GBS.

There are currently no vaccines or medicine for Zika other than the prevention of the mosquito bite. The CDC advises to treat the symptoms and avoid aspirin or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatories to reduce the risk of bleeding until dengue can be ruled out.

Zika can be detected by blood or urine tests. In Norway, these tests are analysed by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH or Folkehelseinstituttet). The virus can also be detected in semen but these tests are not yet available in Norway. NIPH is advising pregnant women not to travel to areas with ongoing increasing incidence of Zika and Individuals who have visited the affected areas should avoid pregnancy during or shortly after the visit.

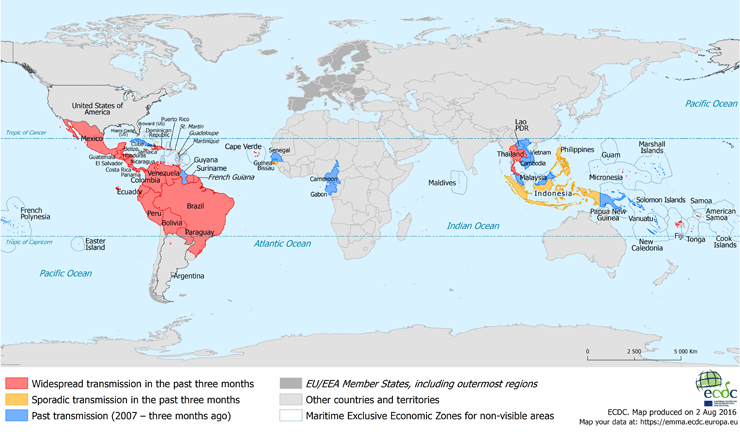

The spread of the Zika epidemic

The Zika virus was first isolated in Africa in 1948 and has since been endemic in parts of Africa and Asia. The initial outbreaks of Zika appeared sporadically and were self-limited. The first outbreak was recorded on Yap Island, Micronesia in 2007[1], following a reemergence in French Polynesia and other Pacific Islands between 2013 and 2014[2]. Brazil first encountered cases of Zika after hosting the 2014 Va’a World Sprint Championship, in which teams from regions where the virus was active were competing[3]. By May 2015, the public health authorities of Brazil confirmed local transmission of Zika virus[4] and, to date 1,687 cases of microcephaly and other birth defects linked to the virus have been reported in the country[5].

Active transmission of the virus continued through mid-spring 2015 (Southern Hemisphere) and peaked in summer 2016, when mosquitos were most active. The latest areas to have been affected are Florida, the Caribbean islands, certain regions of Central and South America, Oceania and Pacific Islands (Papua New Guinea, Micronesia, New Caledonia, Fiji, Tonga, Samoa) and regions in South East Asia (Thailand)[6],[7].

To date in the US the CDC recorded 1,404 cases of Zika with 400 cases of pregnant women infected and 12 infants born with birth defects and a further 6 pregnancy losses that can be linked to the virus[8].

Zika in Norway

In Norway, out of 222 tested individuals, 2 were found to have active infection and 10 were recovering from the virus. No new cases were identified since April 11th 2016.

Where will the virus go next?

Peter Hotez, the Dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor, had previously predicted that the virus has probably already made its way to the U.S. Gulf Coast where it’s likely to cause a lot of damage[9],[10]. In fact, since then the virus had been announced in the North of downtown Miami in Florida, with 14 new cases (2 women and 12 men) confirmed to be infected by local mosquitoes. This number is expected to be much higher, as 6 out of the 10 individuals announced on the 1st of August were asymptomatic and were identified from a door-to-door community survey. Professor Hotez also warns about the high chances of the virus spreading to Southern Europe where it has the opportunity to flourish in the warm Mediterranean climate[11].

What we can learn from the Zika epidemic

A rise in vector-borne neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) such as Zika could become the rule, rather than the exception. NTDs survive and thrive in poverty stricken populations. Low standards of living, no access to healthcare and the limited capacity of states to lift the health standards of their population maintains a disease pool in low- and middle-income countries[11]. However, with the warming climate creating more hospitable environments for NTDs, rapid population growth and increase in migration, travel and transport around the world, we could be seeing a lot more diseases that had been confined to certain regions of the globe stretching their tentacles to previously unaffected populations[11]. Experts advise to increase preparedness, surveillance and training of medical staff to avoid a global disaster as they continue in the efforts to research prevention, transmission and treatment for the virus. For individuals, the CDC advises that it is best to stay away from Zika hot-zones, avoid mosquito bites with insect repellents and practice safe sex.

References

- [1] Duffy MR, et al. (2009) Zika Virus Outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. The New England Journal of Medicine. 360:2536-43

- [2] Kindhauser MK, et al. (2016). Zika: the origin and spread of a mosquito-borne virus [Submitted]. Bull World Health Organ E-pub: 9 Feb 2016.

- [3] Musso, D. (2015). Zika Virus Transmission from French Polynesia to Brazil. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 21(10), 1887. http://doi.org/10.3201/eid2110.151125

- [4] Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization. (2015) Zika Epidemiological Update — 7 May 2015. Washington, D.C.

- [5] Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization. (2016) Zika Epidemiological Update — 14 July 2016. Washington, D.C.

- [6] http://www.who.int/emergencies/zika-virus/zika-historical-distribution.pdf?ua=1 accessed 21/07/2016

- [7] http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/healthtopics/zika_virus_infection/zika-outbreak/Pages/Zika-countries-with-transmission.aspx accessed 03/08/16

- [8] https://www.cdc.gov/pregnancy/zika/data/pregnancy-outcomes.html accessed 11/06/2018

- [9] Hotez PJ (2016) Zika in the United States of America and a Fateful 1969 Decision. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10(5): e0004765. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004765

- [10] http://www.politico.com/story/2016/06/zika-could-cause-billions-of-dollars-of-damage-to-gulf-coast-expert-warns-224106#ixzz4B6Samh6b accessed 21/07/2016

- [11] Hotez PJ (2016) Southern Europe’s Coming Plagues: Vector-Borne Neglected Tropical Diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10(6): e0004243. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004243