In our bodies, we have cells that produce and release antibodies following an infection or vaccination. The production of antibodies is one of the most important components of the immune system. The traditionally, we have though that plasma cells in the bone marrow provide us with long-term protection.

In an exciting study, researchers at the Centre for Immune Regulation (CIR) at the University of Oslo discovered that plasma cells could persist in the human intestine for decades.

The finding challenges one of our most basic conceptions concerning immune response in the body, and it may change treatment of gastrointestinal illnesses.

Traditional bone marrow immunity

– The established notion in medicine has been that the plasma cells that offer life-long immunity are located exclusively in the bone marrow, states postdoctoral fellow at CIR, Ole J. B. Landsverk.

The fact that plasma cells secrete protective antibodies in the bone marrow is the basis for many vaccination strategies. During vaccination, you normally get an intramuscular injection that is expected to give you long-term immunity.

– Then, when you are exposed to something that resembles the vaccine, the antibodies will recognize and neutralize the intruder and will protect you from becoming ill, the researcher explains.

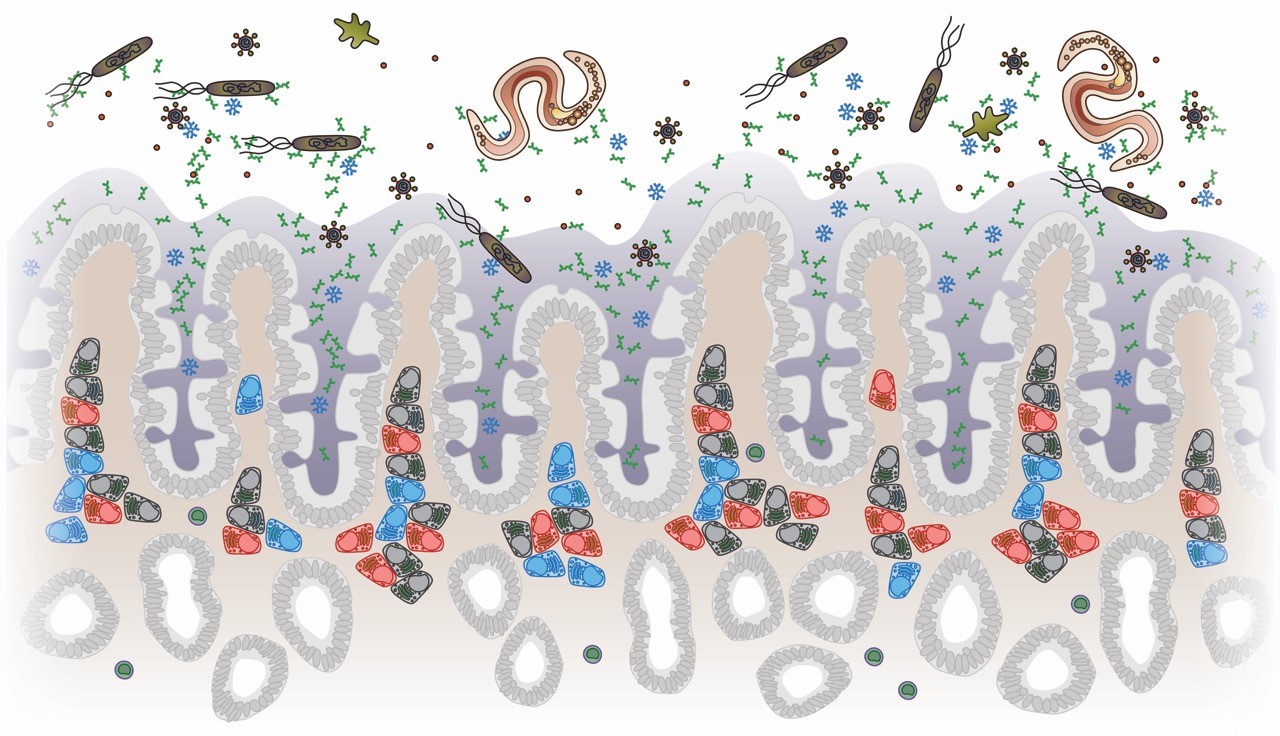

To the same degree, you also have antibody-secreting plasma cells in the intestines.

The intestine is continually exposed to an ever-changing flora comprised of what we eat and drink. The plasma cells in the intestines provide crucial protection against dangerous microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi and viruses, as well as toxins.

– To ensure immunity and remain in control, the intestine must continually adapt to the fluctuating intestinal flora. It does this by constantly developing new plasma cells, Landsverk says.

Until recently, the consensus among researchers has been that plasma cells in the intestinal tract, like the environment in which they live, renew very rapidly, and considered as very short-lived. Thus, it has been deemed pointless to try to develop vaccines that work in the human intestine.

However, the researchers at CIR have now discovered that protective plasma cells can live in the intestine for decades. They arrived at this finding by applying two different methods of analysis.

Cell change investigation after transplants

Firstly, they analysed cells from transplants of the pancreas. The researchers took tissue samples from the segment of intestine attached to the transplanted pancreas to examine any cell changes.

By scrutinizing sex chromosomes, the researchers were able to distinguish old donor cells from new recipient cells in the patient. They were able to do this when the donor organ came from a female (XX) and the patient receiving the donor organ was male (XY).

– We anticipated that the plasma cells in the transplanted part would be quickly replaced so that the organ would adapt to its new environment, and that all the plasma cells would have XY chromosomes, the researcher explained.

The finding was surprising. The researchers found, on the contrary, that most of the plasma cells continued to have female XX chromosomes, even one year after the transplant.

This proved that plasma cells in the intestine survive at least one year and potentially very much longer.

Dating based on nuclear bomb test blasts

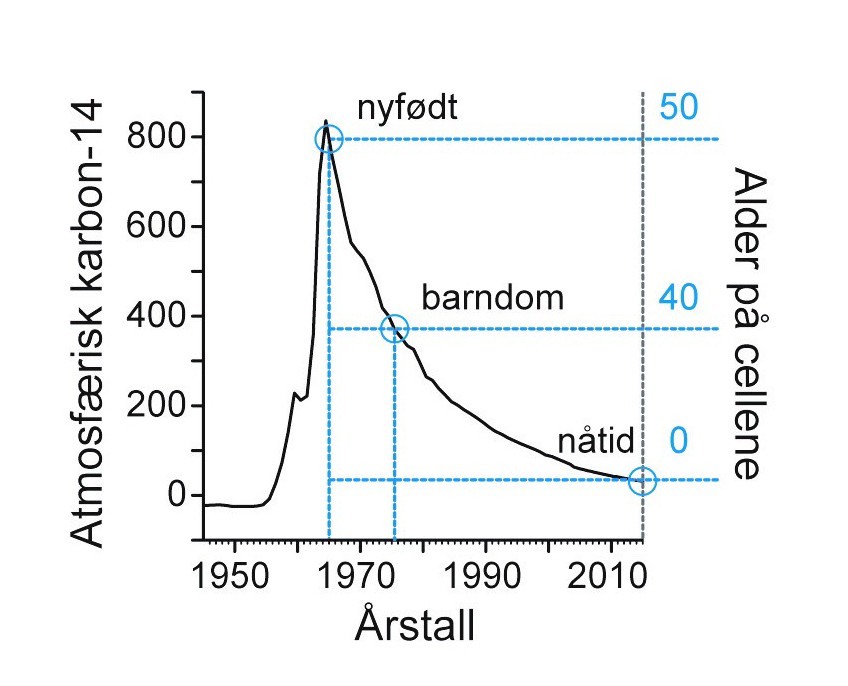

Next, the CIR researchers estimated the age of the cells by using radiocarbon dating. This is a method for dating organic material.

– This method that proves without a doubt that these plasma cells are very long-lived, is based on the atomic bomb tests conducted during the 1950s, Landsverk explains.

– During these trial nuclear blasts, a lot of radioactive carbon 14 was emitted into the atmosphere, but the amount declined dramatically after the signing of a United Nations ban in 1963 ended nuclear bomb testing. Cells that were generated after 1963 will have a lower amount of carbon 14 in their DNA than cells generated when the level was at its peak, he explains.

DNA, or the hereditary material you have in your body, is very stable, as opposed to proteins and most other cell components. The researchers therefore isolated the DNA and measured how much radioactive carbon the cells contained.

– When a cell has a large amount of carbon 14, it would have to have been created at a time when there was a lot of carbon 14 in the atmosphere. This is an effective method, because it is indisputable that the cells are old, the researcher says.

Potential vaccines in pill form

Centre Director at CIR and co-author of the article, Ludvig Sollid, is convinced that this is an important and convincing study:

– This study, in contrast to previous notions, shows that plasma cells in the intestine can live for a long time – perhaps from a person’s childhood years up until old age. The finding is significant for many reasons, including that one should be able to get long-term immunity through vaccination against pathogenic materials in the intestinal tract, Sollid says.

This means in practice that you have an intestinal system that is stable over time and that is equipped to provide significant protection. This may be important in the treatment of intestinal illnesses and autoimmune disorders such as coeliac disease and Chron’s.

The study also offers the possibility of being able to develop vaccines in pill form. Ole J.B. Landsverk hopes that the pharmaceutical industry will focus on developing pill vaccines in the future.

– This can potentially yield vaccines that may be much more effective against intestinal diseases than traditional syringe-injected vaccines, the researcher concludes.

The study was published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine in January 2017.